Self-coherence is a disposition of the soul where your Self—your guiding principle or rational nature—is united with universal Reason, universal Nature, and humanity as a whole. Self-coherence is the fulfillment of the Stoic maxim “live according to Nature.” Pierre Hadot described it as “the fundamental intuition of Stoicism”1; a state of congruity, unity, and coherence between that which “generates reality” and that which “regulates human thought and conduct.”2

Stoicism offers a method to achieve self-coherence. It provides a prescription for a life free of psychological distress—a flourishing and happy life achieved through the pursuit of human excellence. The path of Stoicism is the path of the sage and, while it includes the study of logic, physics, and ethical theory, its process and aim is not primarily academic. The Stoic philosopher is a practitioner. As such, he must learn to live logic, to live physics, and to live ethics.

While Stoicism is a philosophy, it is often referred to as an art of living—a way of life.3 Founded in ancient Athens during a time of social and Geo-political upheaval, Stoicism became a dominate influence in Hellenistic Greece and later in the Roman Empire. The origin of Stoicism was not in the academic world of rhetoric, sophistry, and syllogisms; it was birthed and nurtured under the painted Stoa (porch) of an Athenian marketplace—a “place for the activities of civil magistrates, shopkeepers, and others.”4 Stoicism does not offer a retreat from physical reality, society, pain, or death. Instead, it prescribes a way of life, a way of thinking, which allows one to achieve human excellence and happiness in the midst of the human experience.

Stoicism survives today largely because of the teaching of Epictetus, the slave turned philosopher; the personal journal of the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius; and the prolific writings of Seneca, a Roman Senator. Within those writings one can find a practical guide for living which resonates with the human psyche as strongly today as it did more than two millennia ago.

The late French philosopher Pierre Hadot is renown for his ability to pull philosophy down from the esoteric clouds of academia and make it accessible and applicable to the lives of the non-specialist. This essay presents Hadot’s concept of self-coherence5 as a path toward human excellence for those who seek happiness through a life lived according to Nature. While the synthesis herein is my own, the influence of Hadot will be obvious to anyone who has read The Inner Citadel.

I hope the following pages give you a glimpse of the power of self-coherence and provide some direction to get you started on the path toward that disposition with Nature which culminates in the realization that your rational nature is as a fragment of the rational Nature which orders the entire universe. From that disposition of self-coherence, Marcus Aurelius was able to live these eloquent words he wrote:

Everything suits me which suits your designs, o my universe. (Meditations 4.23)

The Concept of Self-Coherence

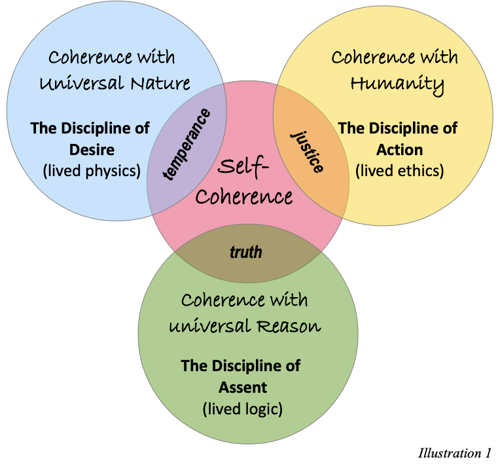

Self-coherence occurs when your Self—your guiding principle or rational nature—is united with, or in agreement with universal Reason, universal Nature, and humanity. Thus, self-coherence is another way of conceptualizing the Stoic maxim “live according to Nature.” Self-coherence relies on three disciplines to cohere the Self with three different aspects of reality and produces three virtues within the practitioner.

Coherence with universal Reason, achieved through the discipline of assent, creates an “inner citadel”6 within the psyche where the Self is circumscribed and protected by the impenetrable walls of Epictetus’ distinction between those things which are in our control and those which are not.7 The first and critical hurdle is the quieting of the psychological tumult, created by the passions, which ravishes the psyche of the fool. Only then, can the Self—your guiding principle—begin the process of cohering with universal Reason.

The discipline of assent guides you in the quest for truth. It results from the ongoing and dynamic expansion of human understanding through rational means—a process which continues to seek new knowledge about human nature and universal Nature. The discipline of assent teaches you to rely upon your rational nature to build an organized and structured conception of self and universal Nature. Coherence with universal Reason—lived logic—produces the virtue of truth.

Coherence with universal Nature, achieved through the discipline of desire, inspires a sense of reverence for creation and the natural laws that regulate the cosmos. This sense of reverence is a dutiful respect for parents, the laws of society, and Nature. Coherence with universal Nature results in acceptance of your destiny. It involves understanding and accepting your place and role within the grand scheme of Nature. Coherence with universal Nature—lived physics—produces the virtue of temperance.

Coherence with Humanity, achieved through the discipline of action, drives you to seek justice in all your human interactions. Your actions are within your control and they are also causal events within the web of causes involving others, society, and humanity as a whole. Thus, your daily actions contribute to justice or injustice. The link between your actions and those closest to you, like your family and friends, is intuitive. However, as a citizen of the world, you must expand their frame of reference and consider how your actions affect others around the world. Coherence with Humanity—lived ethics—produces the virtue of justice.

The Three Disciplines

Self-coherence is achieved through the practice of three Stoic disciplines referred to frequently within the Discourses of Epictetus and the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius. These three disciplines are the discipline of assent, the discipline of desire, and the discipline of action; they correlate with the study of logic, physics, and ethics respectively. The three disciplines of Stoicism are designed to transform the foolish, lost wanderer into a progressor,8 capable of appropriate action, as he travels the path of the sage toward a life of excellence (virtue) and happiness.

The disciplines of assent, desire, and action are interrelated. None can be practiced entirely isolated from the other two; thus, while you may be focused on one of the disciplines at a given time, the other two disciplines are necessarily involved in every step the progressor takes. The practice of these disciplines is an iterative process were technical understanding and practical application are inseparably intertwined and synergistic.

Nevertheless, Epictetus asserts that controlling our passions, through the discipline of desire, is the “most urgent” of the three exercises for two reasons. First, our unnatural desires and aversions, those which are incongruous with universal Reason and universal Nature, are the source of crippling psychological disturbances. Secondly, until our most ardent desires and aversion are controlled, we are “incapable of listening to reason” (Discourses 3.2.3). Universal Reason cannot reach the guiding principle within the mind of a complete fool, driven by passions. Epictetus meets the fool where he stands—in the midst of a whirlwind of passions—where a cacophony of noise prevents him from hearing the quiet voice of universal Reason, where ever present distractions blind him from the truth of universal Nature which surrounds him. Epictetus realizes the fool must step outside the tumult of life’s passions before he can take the first step on the path toward human flourishing (happiness).

However, attempting to quell the passions without the discipline of assent is akin to attacking a raging forest fire with a bucket brigade. The flames are far too hot and the fuel too plentiful for such an effort to have an impact. Thus, like modern fire fighters who cut a firebreak around a blaze to deny it more fuel, we must circumscribe the Self through the discipline of assent and thereby begin starving the flames of our passions, which are fueled by false judgments.

Before diving into the three disciplines, it is helpful to understand how they relate to each other and to Stoic philosophy in general. Table 1 is consolidated from two of Hadot’s books.9 It brings many of the supporting concepts together and illustrates the relationships between the technical and practical aspects of the three disciplines of Stoicism.

| Discipline | Domain of Reality | Field of Study | Inner Attitude | Corresponding Virtue |

| of assent | faculty of judgment | Logic | objectivity | Truth (aletheia); absence of hasty judgment (aproptosia) |

| of desire | universal Nature | Physics | consent to destiny | Temperance (sophrosyne); absence of worries (ataraxia) |

| of action | our Nature | Ethics | justice and altruism | Justice (dikaiosyne) |

Below are passages from Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius which directly relate to the three disciplines. The blue text within parenthesis was added to relate the passages to each of the Stoic disciplines.

The three disciplines are outlined by Epictetus as follows:

- There are three areas of study or exercise, in which a person who is going to be good must be trained. That concerning desires and the aversions, so that he may neither fail to get what he desires nor fall into what he would avoid (discipline of desire).

- That concerning impulse to act and no to act, and, in general, appropriate behavior; so that he may act in an orderly manner and after due consideration, and not carelessly (discipline of action). The third is concerned with freedom from deception and hasty judgment, and, in general whatever is connected with assent (discipline of assent).

- Of these, the most urgent, is that which has to do with the passions (discipline of desire); for these are produced in no other way than by the disappointment of our desires, and the incurring of our aversions. It is this that introduces disturbances, tumults, misfortunes, and calamities; and causes sorrow, lamentation and envy; and renders us envious and jealous, and thus incapable of listening to reason.

- The next has to do with appropriate action (discipline of action). For I should not be unfeeling like a statue, but should preserve my natural and acquired relations as a man who honours the gods, as a son, as a brother, as a father, as a citizen.

- The third falls to those who are already making progress and is concerned with the achievement of certainty in the matters already covered, so that even in dreams, or drunkenness or melancholy no untested impression may catch us off guard (discipline of assent). (Discourses 3.2.1-5)

The three disciplines are repeatedly stressed by Marcus Aurelius in his Meditations:

7.54 Everywhere and all the time it lies within your power to be reverently contented with your present lot (discipline of desire), to behave justly to such people as are presently at hand (discipline of action), and to deal skilfully with your present impressions so that nothing may steal into your mind which you have not adequately grasped (discipline of assent).

8.7 Every nature is contented when things go well for it; and things go well for a rational nature when it never gives its assent to a false or doubtful impression (discipline of assent), and directs its impulses only to actions that further the common good (discipline of action), and limits its desires and aversions only to things that are within its power (discipline of desire), and welcomes all that is assigned to it by universal nature.

9.6 It is sufficient that your present judgement should grasp its object (discipline of assent), that your present action should be directed to the common good (discipline of action), that your present disposition should be well satisfied with all that happens to it from a cause outside itself (discipline of desire).

9.7 Blot out imagination (discipline of assent); put a curb on impulse (discipline of action); quench desire (discipline of desire); ensure that your ruling centre remains under its own control.

4.33 What, then, is worthy of our striving? This alone, a mind governed by justice, deeds directed to the common good (discipline of action), words that never lie (discipline of assent), and a disposition that welcomes all that happens, as necessary, as familiar, as flowing from the same kind of origin and spring (discipline of desire).

Read the full essay here:

https://library.collegeofstoicphilosophers.org/Self-Coherence-final.pdf

- Pierre Hadot, The Inner Citadel (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press , 1998), 130

- Ibid

- John Sellars, The Art of living (London: Duckworth, 2009); and Hadot, The Inner Citadel

- The Stoa, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, http://www.iep.utm.edu/stoa/

- Hadot, The Inner Citadel, 130

- Ibid., 107

- Epictetus Encheiridion I

- Tad Brennan uses the term “progressor” and I thinks it contributes to the dialogue about Stoicism as a practice. Tad Brennan, The Stoic Life (Oxford, 2005)

- Hadot, The Inner Citadel, 44; and Philosophy as a Way of Life (Oxford:Blackwell, 1995), 198