1. Negotiating Stoicism

1.1 Two Techne

Over the past few decades, the communications technologies employed by societies around the world have advanced at a staggering rate. Despite this, or perhaps owing to it, the ability of those societies to communicate well seems to have suffered. This is because, much like classical philosophy, skillful communication is a set of enacted principles—a techne. It cannot be bought or downloaded. Until it is owned through practice, it is merely sounds in the air, ink on paper, or pixels on a screen. My goal is to compare some of the best practices of skillful communication, particularly those of negotiation, with classical Stoicism as an applied philosophy. The intention is twofold. First, it is to determine in what ways the two are compatible in principle. Second, it is to identify how they can supplement and complement one another in practice.

1.2 Negotiations fit for a Stoic

Not knowing what image the reader has of negotiation, allow me to take a moment to salvage it as a practice befitting a Stoic. While negotiation is a tool and, as with any tool, can be turned to unvirtuous ends, its most powerful practices are inconsistent with selfish and/or malevolent motivations. At its best, negotiation is a form of skillful communication characterized by empathy, mutual understanding, and principle. It does not frame others as obstacles to be overcome or pawns to be manipulated. Rather, it is a discipline, the proper practice of which, naturally strengthens character as it develops capability.

Negotiation is the undercurrent, and occasionally the riptide, of every human-to-human interaction. Becoming a better negotiator means becoming a more effective human. Stoics do not live their lives inside the walled garden. They pursue wisdom, justice, courage, and temperance in the messy arenas of the world. It is precisely in these arenas that the skill of negotiation proves its worth.

1.3 Academic vs. Applied Negotiation

The first question to answer regards the state of negotiation as a field of study. Much academic work has been done over the past few decades with notable contributions such as Kurt Lewin’s change model (1947), Morton Deutsch’s win-win (1973), and concepts such as Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement (BATNA) which Roger Fisher and William Ury (2011) described in Getting to Yes, the most-read negotiation book of all time. But, more recently, the validity and completeness of academically-produced, theoretically-rooted approaches such as these has been called into question by career negotiators such as Jim Camp, George Thompson, and Chris Voss.

While the academic scholarship emphasizes rationality and logic, these professional communicators tend to highlight the emotional dimension of human interactions. It is their approaches that will be my primary focus. It is, after all, from people such as hostage negotiators (Voss) and beat cops (Thompson) that the Stoics themselves would have wanted to learn.

Additionally, while Stoicism conceives of humans as fundamentally rational creatures, rationality is often a state achieved only after overcoming the hurdles of emotionality. This, then, is the first of the parallels we will draw between negotiation and Stoicism: they both seek to access the rationality of self or other by recognizing and addressing the emotionality that typically precedes and regularly besieges it.

2. Overlapping Principles

2.1 Emotional Control

“…make the distinction first between being in control and being controlling…. Being in control in conversations means having the ability to govern all of your behavior and thoughts to keep them natural, controlled, and calm…” (Hughes, 2017, p. 122-3).

The skilled negotiator exhibits a high degree of emotional control, but not a lack of emotion. Similarly, recognizing it as both unfeasible and unvirtuous, the Stoics did not prescribe an emotionless or non-reactive existence. Nevertheless, they maintained that, in accord with the disciplines of assent and action, emotions could be acknowledged without being indulged—they could be experienced without being overwhelming. “We, however, may be forgiven for bursting into tears if only our tears have not flowed to excess, and if we have checked them by our own efforts” (Seneca, 2016, p. 148). Camp makes the same point: “I couldn’t absolutely control my emotions—no one can—but I could keep them under check, I could keep them from overly influencing my actions, with carefully constructed behavioral habits” (2002, p. 11).

This capacity is of such great importance when negotiating for several reasons. First, maintaining emotional control allows the negotiator to remain rational. “Common sense is most uncommon under pressure…. Keep your cool and you’ll maintain your common sense” (Thompson & Jenkins, 2004, p. 222). This state will also prove contagious.

If a negotiator wants the other party to remain unemotional and capable of rational deliberation, they must embody this state first. Voss suggests using what he calls the “Late-Night, FM DJ Voice”—a deep, soft, slow, and reassuring tone of voice coupled with downward inflections—to project calm and reasonability, remarking that it is not what we say but “…how we are (our general demeanor and delivery) that is both the easiest thing to enact and the most immediately effective mode of influence” (2016, p. 31). One need not be emotionless. But regularly taking account of one’s emotional state should be habitual and behavioral interventions with the power to alter that state should be well-practiced.

Second, a negotiator with control of their emotions makes a better impression.

Possessing the ability to control yourself, to remain calm and caring, will change your results if you do nothing else…. Having the ability to follow through and completely control yourself when needed creates a mental state that subconsciously broadcasts your confidence and personal authority (Hughes, 2017, p. 122-3).

In addition to the presence conferred by such self-control, it makes available tools such as mirroring—repeating the other party’s last one to three words with an upward inflection—which can be used to gain more information and rapidly develop rapport. The more a negotiator projects their emotions the less they will be able to reflect those of the other party.

And, third, emotional control allows the negotiator to be curious. The work of the negotiator lies, not in convincing, but in investigating. According to Camp, “You cannot tell anyone anything…. You can only help people see for themselves” (2002, p. 175). This is why, according to him, the negotiator’s job is to understand the other party’s pain so that pain can be re-presented in a way that helps the other party understand what needs to be done. To this end, negotiators want as much information about the other party and the relevant context as they can manage. Passionate emotion is not conducive to curiosity, contributing instead to logical leaps and unfounded assumptions.

2.2 Non-neediness

“Everyone is subject to anyone who has power over what he wants or doesn’t want, as one who is in a position to confer it or take it away” (Epictetus, 2014, p. 291). The skilled negotiator neither experiences nor communicates neediness. Regardless of how the negotiation progresses, the negotiator is not bound to securing any pre-identified outcomes. Camp makes a point of distinguishing between true needs and mere desires. The former are rare and, in many cases, overlap with what Stoics identify as moral goods. The latter, translated into the Stoic vernacular, are preferred indifferents. Epictetus instructs: “Do not tell yourself that indifferent things are necessary to you, they will no longer be so” (qtd in. Hadot, 1998, p. 110). You may realize an outcome you prefer or you may not, and nothing of true consequence depends on it. Just as with the Stoics, the skilled negotiator does not allow desire for an outcome to compromise their character or principles.

Faced with a dispreferred outcome, the Stoic follows Marcus Aurelius’ advice: “Stick with the situation at hand, and ask, ‘Why is this so unbearable? Why can’t I endure it?’ You’ll be embarrassed to answer” (2002, p. 108). This psychological posture gives the negotiator a position of advantage. The less attached they are to achieving any particular outcome, the more flexibility and leverage they possess.

A particularly insidious problem related to neediness arises when the negotiator’s egoic needs become a factor. An example is when the negotiator’s desire for self-validation becomes the motive force behind their behaviors. Hadot quotes Monimus saying, “Pride is a dreadful sophist, and it is just at the moment when you think you are devoting yourself to serious matters that it enchants you the most” (1998, p. 56). The desire to be important can make any negotiation seem serious; the seriousness of the negotiation can delude the negotiator into believing they are owed what is not under their control. Striving to decrease neediness should begin with one’s own ego as this is doubtless the negotiator’s most potent foe.

2.3 Process-focused

Related to this non-attachment to outcomes is a focus on the quality of one’s process. According to Voss, “…negotiation is more like walking on a tightrope than competing against an opponent. Focusing so much on the end objective will only distract you from the next step…” (2014, p. 220). For comparison, Marcus Aurelius wrote of the Stoic, “He does only what is his to do… doing his best, and trusting that all is for the best. For we carry our fate with us—and it carries us” (2002, p. 29). Both advise against looking ahead to potential future outcomes, instead suggesting that our resources are best channeled into skillfully enacting the process. Not only can outcome-seeking lead to errors in the present, but it can promote shortcuts and compromises, including those of the ethical kind. Only when the end is preferentially valued can it justify the questionable means used to achieve it. A Stoic would point out that these process elements are, in themselves, the most crucial, consequential of actions. “The sage desires only that he should do what he can to the best of his ability, no more and no less, and he accepts success or failure with equal serenity because he concerns himself only with the quality of his actions, and not their results” (Robertson, 2010, p. 235).

While the outcome of a negotiation can be more-or-less preferred, it is by its nature an external event and therefore, one which the Stoics would argue lacks the moral implications that attend any choices made in securing it. Such outcomes are, after all, largely products of uncontrollable external events. The negotiation literature offers a complimentary argument: you cannot make moral compromises and still project the character needed to negotiate well. “Any part of your life that isn’t congruent with the image you wish to project will eventually leak out in your behavior on an unconscious level” (Hughes, 2017, p. 121). This is the importance of integrity, which describes a person who is “…blended into a whole, as opposed to a person of many parts, many faces, many disconnects. The word relates to the ancients’ distinction between living and living well” (Stockdale, 1995, p. 117).

The skilled negotiator focuses on the process, demonstrating skill at each stage with each behavior; the Stoic attends to the present—prosochē—manifesting virtue through desire, assent, and action. Whereas Camp (2002) uses the analogy of the batter who hits more home runs by focusing on the quality of their swing, the Stoics recognize that the archer who aims and shoots with great skill may not always hit the target, but achieves something of value nonetheless. “It is not the result, but the spirit with which you pursue your just ends that really counts” (Stockdale, 1995, p. 73). While a sound process, enacted proficiently, will not always result in the preferred outcome, it both increases the odds and contributes to the development of both the practitioner’s expertise and character.

2.4 Embrace No

Related to this lack of outcome-attachment is the need to embrace “no”. One of the most counterintuitive elements highlighted by master negotiators such as Camp and Voss is the power of getting the other party to say “no”. “For good negotiators, ‘No’ is pure gold. That negative provides a great opportunity for you and the other party to clarify what you really want…. ‘Yes’ and ‘Maybe’ are often worthless. But ‘No’ always alters the conversation” (2017, p. 75).

“No” is the beginning of the negotiation because, as Camp (2002) points out, it provides the other party with the feeling of being in control, able to avoid unwanted outcomes and, thus, safe to explore the possibilities—a core factor contributing to the quality of a negotiation. Get “no” out of the way early and invite it often to reinforce the feeling in the other party that they are leading the negotiation rather than being bullied or tricked. Voss (2017) suggests encouraging “no” with well-worded questions such as, “Have you given up on working this out?” or “Would it be crazy to think we can find something that works for everyone?” But the core of this skill lies in appreciating that “no” often creates more possibilities than “yes”.

This principle connects to Stoicism in two ways. First, there is the degree of imperturbability needed to apply it. Seeing external events for what they are—as mere indifferents—helps lighten the impact of hearing “no” when your desire is for “yes”. “…no one is master over another person’s choice” (Epictetus, 2014, p. 274). Second, one function of eliciting and inviting “no” is to satiate the other party’s emotional needs. Once they feel in control, you can begin speaking to their rational mind. This is a strategy for aiding the other party’s rationality while improving the relationship.

2.5 Take Care of the Other Party

“He keeps in mind that all rational things are related, and that to care for all human beings is part of being human” (Aurelius, 2002, p. 29). A good negotiator takes care of the other party in two ways, by making them feel alright throughout the process, and by seeking out agreements that will strengthen the relationship moving forward. Embracing “no” is one way to contribute to the first of these. A second is offered by both Hughes (2017) and Camp (2002) who suggest that the negotiator take the extra step of making themselves seem not okay. This allows the other party to enjoy the relative well-being associated with being the more okay of the concerned parties. Steps to achieve this might include appearing unprepared or adopting a slightly unkempt appearance. The goal is not to deceive the other party, but to help them feel comfortable. “If you want to make progress, put up with being thought foolish and silly with regard to external things, and don’t even wish to give the impression of knowing anything about them” (Epictetus, 2014, p. 290).

This was an indispensable element of Socrates’ toolkit as he professed ignorance about topics in one breath only to ask incisive questions about them in the next. The goal is to avoid the interaction becoming a contest of who is right. “...one of the worst habits you can fall into when drawn into a verbal confrontation is to switch to a speech or debate mode” (Thompson & Jenkins, 2004, p. 61). The most reliably lasting effect of showing someone that they are wrong and you are right is the negative association you have attached to yourself. All you have convinced them of is to avoid speaking with you again. The skilled negotiator wants the other party’s ego to be safe and satisfied.

The other party’s comfort and satisfaction also rely, perhaps more than any other factor, on their feeling heard. Listening is not enough, nor is genuinely hearing them—they must feel that you have heard them. This requires empathy. “…staying calm in the middle of conflict, deflecting verbal abuse, and offering empathy in the face of antagonism. If you cannot empathize with people, you don’t stand a chance of getting them to listen to you…” (Thompson & Jenkins, 2004, p. 67). Empathy is at the core of the systems being discussed here. It is how bridges are initially built, how relationships are maintained, and how acceptable outcomes are identified.

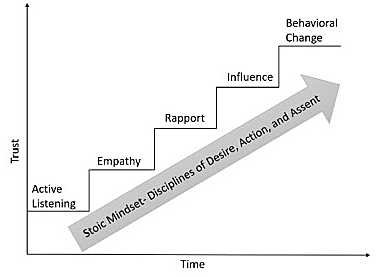

Developed based on findings from real-world hostage negotiations, the Behavioral Change Stairway Model (Vecchi et al, 2005) depicts this process. This version has been modified to depict how Stoicism can support the process depicted.

The second way in which the skilled negotiator takes care of the other party is in the final terms they pursue. A deal that leaves the other party feeling fleeced may feel like a win at first, but even excepting the virtue concerns of a Stoic, the negotiator must consider how this outcome will affect their relationship with the other party. “We were born to work together like feet, hands, and eyes, like the two rows of teeth, upper and lower. To obstruct each other is unnatural. To feel anger at someone, to turn your back on him: these are obstructions” (Aurelius, 2002, p. 17). Negotiating such that the concerned parties—complementary parts that they are—are left unable to work together would ultimately serve no one. Every negotiation should leave the relationship in a better place. In such cases, the negotiator and the Stoic can be sure of improving both their standing and their character.

2.6 Accusation Audit

The next principle can be effectively summarized by Epictetus: “If someone reports to you that a certain person is speaking ill of you, don’t defend yourself against what has been said, but reply instead, ‘Ah yes, he was plainly unaware of all my other faults, or else those wouldn’t have been the only ones that he mentioned” (2013, p. 298). Voss (2017) calls this an “accusation audit” and suggests it be used to preempt all the negative characterizations the other party might level at you or your position. If, for example, the negotiator backed out of a previous agreement, they might begin by saying, “I know you probably think I’m totally unreliable.” Doing this accomplishes several things. It demonstrates consideration for the other party and their perspective while taking away the weapons they might otherwise have used. It places the negotiator at a seeming disadvantage, allows the other party to feel in control, and invites them to come to the defense of the negotiator—inviting a “no”. It puts out in the open elements that would have otherwise been functioning in the background, shining light on how they are influencing the process.

The negotiator is thus able to better account for them, and even to get them working in his or her favor. “When you’ve decided that you ought to do something and are doing it, never try to avoid being seen to do it, even if most people will probably view it with disapproval” (Epictetus, 2014, p. 299). Running from how the other party perceives you only confirms that perception. Preempt the characterization to nullify it.

As the word “audit” suggests, the negotiator must be thorough. They would be best served adhering to the Stoic maxim that, “If something is right or wrong, good or bad, then there are no degrees of goodness…. All bad actions are equally bad… no matter how serious or trivial they may appear to be” (Sellars, 2004, p. 112). And, in cases where the negotiator is not thorough enough, the other party can, with the right mindset, become a valued resource. “One should pay attention to one’s enemies, for they are the first to detect one’s errors” (Laertius, 1853, p. 221).

Being process- rather than outcome-focused drives the Stoic and the negotiator to value opportunities for improvement more than routes to victory. Neither skilled negotiators nor practicing Stoics retreat from their flaws. Rather, they seek them out. If you have little to offer, say “I have an offer that probably won’t interest you”.

If you need to make an unreasonable request, begin with “I need to ask for something that you’ll never agree to”. “The impediment to action advances action. What stands in the way becomes the way” (Aurelius, 2002, p. 60).

2.7 Questions & Listening

“Negotiation is not an act of battle; it’s a process of discovery” (Voss, 2017, p.47). One would be hard pressed to find a better exemplar of this principle than Socrates. The core of negotiation is not speaking, but humbly asking questions and listening with genuine curiosity to the answers. “Remain silent for the most part, or say only what is essential, and in few words” (Epictetus, 2014, p. 297). The mindset is that of a detective seeking to discover everything that is both relevant and hidden. But, this requires a type of skilled listening that must be cultivated.

Listening is not a natural act. It is highly artificial and artistic…. Listening is not the opposite of talking…. The opposite of talking is more like waiting to interrupt. Active listening is a highly complex skill that has four different steps: Being open and unbiased, hearing literally, interpreting the data, and acting” (Thompson & Jenkins, 2002, p. 115).

At the core of such listening is dedicated attention, because the negotiator needs to hear more than what is said—they need to hear what is meant. “Never react to what people say. React to what they mean. Just remember: People hardly ever say what they mean” (Thompson, p. 119). This is consistent with Stoic teachings since reacting to the other party’s words without consideration would violate the discipline of assent. “Try above all, then, not to allow yourself to be carried away by the impression…” (Epictetus, 2014, p. 292). And listening with the intent to understand and empathize requires hearing the message through the words, a feat of dedicated attention. Strive to “…make your sole and all-encompassing focus the other person and what they have to say” (Voss, 2017, p. 47). Listen with prosochē: “…is there anything whatever in life that is done better by those who remain inattentive?” (Epictetus, 2014, p. 273).

As Socrates demonstrates, discovering more about the other party—about their position, motivations, beliefs, etc.—will often lead to their making your case for you. His dialogues provide templates for this process. He asks because he is curious. He listens because he wants to know. He paraphrases the other party’s points to their expressed satisfaction because he does not wish to misrepresent or manipulate. One exchange at a time, he allows the other party to paint a picture of their own lack of understanding.

The negotiator seeks something similar. “Your adversary in any negotiation must have a vision before they can ever take action…. No vision, no action…. But what, exactly do we need a vision of? Pain. This is what brings every adversary in every negotiation to the table” (Camp, 2002, p. 159). This is the pain associated with a thus far unrealized desire for change—whatever is seen as the current or future problem. Ensuring the comfort of the other party, asking genuine questions, and making them feel heard will often lead to their painting a picture of this pain for the negotiator. The result is a blueprint for how the negotiator can provide value, build trust, and influence behavior. Whereas Socrates left people wiser, the skilled negotiator leaves them in less pain.

3. Principles in Practice

Stoicism makes such a good partner for negotiation, not only because of how their principles overlap, but because of the gaps the former is able to fill. As with most worthwhile practices, those of negotiation are conceptually simple but slippery in practice. Paraphrasing the position of someone with whom you disagree or empathizing with someone who is insulting you are technically uncomplicated behaviors. But, at those times when they would be most beneficial, they can feel nearly impossible to remember and/or to do. “…in theory, there is nothing to restrain us from drawing the consequences of what we have been taught, whereas in life there are many things that pull us off course” (Epictetus, 2014, p. 56). While the authors whose works we have explored do a wonderful job explaining what a good negotiator does, on the topic of how one goes from being a novice to possessing any level of skill whatsoever, they are largely silent. As a philosophy that can only be understood when it is lived, Stoicism has much to offer on this point.

3.1 Premeditatio Malorum

“…the proper course with every kind of fear is to think about it rationally and calmly, but with great concentration, until it becomes completely familiar” (Russell, 1930, p. 60). The best way to desensitize oneself to a given stimulus is to experience it. Unfortunately, most people are not afforded the option to engage in an ego-challenging negotiation whenever we like. Were the practitioner able to choose the time and place, both the equanimity they could bring and the exposure over time would lead to the rapid development of many of the skills outlined above. This is where the practitioner can employ premeditatio malorum, or philosophical premeditation, wherein “…we imagine in advance various difficulties, reversals of fortune, sufferings, and death” (Hadot, 2002, p. 137). From Seneca, “We must see to it that nothing takes us by surprise. And since it is invariably unfamiliarity that makes a thing more formidable than it really is, this habit of continual reflection will ensure that no form of adversity finds you a complete beginner” (2004, p. 198).

For example, making the experience of being told “no” by the other party an object of repeated premeditatio malorum visualization can help inure the practitioner to the word’s capacity for exciting the passions. Treating the potential consequences of a “no” as though they were a stalwart companion will help the practitioner accept the possibility of those consequences, thereby dampening the feeling that they are best avoided. “By anticipating certain kinds of abuse and questions… I have taken those weapons away from my opponent” (Thompson p. 142).

Premeditatio malorum is also well suited for making effective communication practices, such as those described above, into habitual ones. Using it to run through the kinds of interactions in which you struggle to respond skillfully such that you reinforce the behaviors you hope to employ is not only effective, it is low-cost and even lower stakes.

Finally, premeditatio malorum employed as the Stoics used it—to become intimately acquainted with illness and death— “…transforms our way of acting in a radical way, by forcing us to become aware of the infinite value of each instant” (Hadot, 2002, p. 137). The implications for negotiation lie in the mindset of the negotiator.

Gratitude is the most powerful feeling you can have…. The depth to which you become grateful will eventually change the way you converse with subjects; you will become able to see past their social masks and gain the ability to think deeply about their demeanors and backgrounds (Hughes, 2017, p. 126).

Internalizing the finitude of one’s individual existence grants every moment infinite value. Gratitude is influence earned through reflection. “…we transform our lives by transforming the habitual dispositions of our souls” (Sellars, 2004, p. 36).

3.2 The Use of Impressions

“Every difference that there can be between one person’s psychology and another person’s psychology can be accounted for entirely in terms of the patterns of assents that they each make” (Brennan, 2005, p. 52). One of Stoicism’s core armaments is the habit of separating impressions—perceptions and the pre-conscious judgments that attend them—from the giving of assent to those impressions. This habit is of the utmost importance for the negotiator whose skill depends largely on 1) detecting meaning through a veil of words, and 2) assenting only to interpretations of that meaning that support the process. “Every situation… presents just another instance in an infinite series of variations on the same fundamental question…’What use am I making of my impressions right now?‘” (Robertson, 2010, p. 159). The negotiator who readily assents to initial impressions based on what was said, without reflecting on the validity of those impressions or their capacity to disturb or derail the process, demonstrates a lack of skill and proper attention.

“Like seeing roasted meat and other dishes in front of you and suddenly realizing: This is dead fish. A dead bird. A dead pig. Or that this noble vintage is grape juice, and the purple robes are sheep wool dyed with shellfish blood” (Aurelius, 2002, p. 70-1). Just as the Emperor sees through the trappings by questioning initial impressions, the negotiator must see through the other party’s obfuscations and misdirections to the raw message underneath. Rosenberg suggested that the essence of any communication can be classified as either “please” or “thank you”—as an expression of pain or gratitude. “…latching onto things and piercing through them, so we see what they really are. That’s what we need to do all the time…” (Aurelius, 2002, p. 71). The negotiator who hears the essence of each communication will not feel insulted or become impatient, but will be capable of both rational and empathetic communication.

3.3 View from Above

In the development of a negotiator, the View from Above serves several crucial purposes. First, it promotes emotional detachment, allowing the negotiator to remain more objective and rational than otherwise. Well-cultivated, this practice allows the negotiator to identify with something grander, “…cultivating a new perspective on the world that tries to see things from the point of view of Nature as a whole rather than merely from one’s own limited perspective” (Sellars, 2006, p. 126). Thereby, the negotiator occupies a powerful psychological position, that of the emissary. “When you speak, you are a mouthpiece, a representative. You do not represent your own ego. Remember, the more ego you show, the less power you have over other people” (Thompson & Jenkins, 2004, p. 107).

Second, it prevents outcome fixation by reminding the negotiator of the much larger system in which the negotiation is taking place. Remembering how tiny and finite each of our existences ultimately are helps to put the gravity of any possible negotiated outcomes into perspective. “Our lifetime is so brief…. Nothing to get excited about. Consider the abyss of time past, the infinite future. Three days of life or three generations: what’s the difference?” (Aurelius, 2002, p. 49).

Third, it broadens the negotiator’s field of possibility, preventing him or her from narrowly understanding what is being negotiated and the ways in which the issue might be resolved. “Great negotiators are able to questions the assumptions that the rest of the involved players accept on faith or in arrogance, and thus remain more emotionally open to all possibilities, and more intellectually agile to a fluid situation” (Voss, 2017, p. 25).

Negotiation gurus Fisher and Ury (2011) suggest four principles of negotiation: separate people from the problem, focus on interests rather than positions, invent options for mutual gain, and base agreements on objective criteria. Practicing the View from Above supports the negotiator in applying each of these principles. It allows for an expanded and more objective understanding of context without which it is easy to get lost in winning battles that can cost the war.

3.4 Determinism

The Stoic doctrine of determinism also has a place in the negotiator’s repertoire, first as a supporting orientation for the development of non-neediness: whatever the outcome, it is the only possible outcome and the necessary one as well. “Don’t seek that all that comes about should come about as you wish, but wish that everything that comes about should come about just as it does…” (Epictetus, 2014, p. 289). The negotiator who embodies amor fati—love of fate—exudes gratitude, embraces “no”, and demonstrates great responsiveness.

But a deterministic outlook offers another, equally important benefit. “Contemplating psychological determinism is a key means of developing human empathy” (Robertson, 2010, p. 240). The negotiator who accepts that people can only have behaved as they did will find no basis for anger or resentment.

To feel affection for people even when they make mistakes is uniquely human. You can do it, if you simply recognize: that they’re human too, that they act out of ignorance, against their will, and that you’ll both be dead before long. And, above all, that they haven’t really hurt you. They haven’t diminished your ability to choose (Aurelius, 2002, p. 88-89).

3.5 Daily Audit

Taking time at the end of each day to review how you behaved will help you to identify the triggers that consistently knock you out of the desired mindset. When journaling, it is important not only to note the behavior you are concerned with, but also the mental state you were in, including any emotional elements, when you behaved thus.

As the practitioner uncovers their triggers and insecurities, these may resolve themselves merely owing to exposure. If not, targeted journaling interventions can also help. One powerful intervention that combines well with journaling is naming the troublesome mental states as you would a pet. Once the state has a name, it becomes easier to recognize and respond to. “Build your trigger guard. Make a list of your most harmful weaknesses. Then name them. Give each a little tag and pin it wriggling to the wall of definition. Then you own them” (Thompson, p. 106).

This approach can further be strengthened by preloading your decisions using “action triggers”. For these to be effective they need to be specific, containing both a triggering event and a desired response (Heath & Heath, 2010). An example would be, “Next time (my boss suggests that I could have done something better), instead of (defending myself) I will (accurately summarize his position)”.

Written statements such as these may work the first time, but this should not be the expectation. Just as Marcus Aurelius did, repetition of key points and principles should be embraced. “One way to assimilate information is to write it out a number of times…” (Sellars, 2004, p. 46). It is important, as well, to write with care. Hadot points out that, What counts is the reformulation: the act of writing or talking to oneself, right now, in the very moment when one needs to write…. The act of composing with the greatest care possible: to search for that version which, at a given moment, will produce the greatest effect, in the moment before it fades away, almost instantaneously, almost as soon as it is written. Characters traced onto some medium do not fix anything: everything is in the act of writing (1998, p. 51).

The result of such rigorous journaling is that the writer spends more time with each line, mentally rolling it around, buffing it, and distilling it. This, in combination with the act of physically writing it out, serves to more deeply imprint each line on its author. The pen and page are the whetstone of the mind —properly used they maintain and sharpen the mental faculties.

3.6 The Dichotomy of Control

At the center of Stoic practice lies the realization that, “Some things are within our power, while others are not” (Epictetus, 2014, p. 287). Habitually asking “Is this under my control?” and adjusting one’s mental posture according to the answer is a change that offers systemic benefits to the negotiator’s capabilities. Staying on top of the internal or external nature of events allows the negotiator to focus their efforts where they are guaranteed to gain purchase: on the things within their control. Developing a tolerance and, eventually, an appreciation for the vicissitudes of negotiation is how neediness can best be curtailed, how “no” can be welcomed, how the process can supersede the outcome. “The birth of my ability to communicate came in my acceptance of the fact that I was the problem” (Thompson, 2004, p. 94). A negotiator can only do their best if they remain focused on the moves available to them. And success filtered through the lens of the Dichotomy of Control is never determined by external events. “You can be invincible if you never enter a contest in which the victory doesn’t depend on you” (Epictetus, 2014, p. 292).

4. Conclusion

Stoicism provides the negotiator with two paths whereby to supplement his or her practice. First, many of the central principles of negotiation overlap with those of Stoicism. Such overlaps offer more than mere reiteration. Seriously explored, they can deepen the negotiator’s understanding, offering different insights and fresh perspectives based on ancient wisdom. Second, Stoicism is a practice whose principles are incomplete when divorced from the methods whereby their skillful application is pursued. As this essay has detailed, many of these methods are immediately applicable to the development of negotiation skill.

For the dedicated Stoic, negotiation is a tool. It is not manipulative or covetous by nature; as with all things of moral consequence, these are internal elements that may find expression through the medium of negotiation. For those committed to the virtues of wisdom, justice, courage, and temperance, negotiation offers great opportunities. Its skilled use requires, by turns, each of these virtues while serving to magnify the influence they enjoy in the world. But none of this happens without action. Both the negotiator and the Stoic are forged in the market, the court, and the arena.

…our powers can never inspire in us implicit faith in ourselves except when many difficulties have confronted us on this side and on that… no prizefighter can go with high spirits into the strife if he has never been beaten black and blue… who, as often as he falls, rises again with greater defiance than ever (Seneca, 2016, p. 25).

Aurelius, M. (2002). Meditations. G. Hays (Trans.). New York, NY: The Modern Library.

Brennan, T. (2005). The Stoic life. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Camp, J. (2002). Start with no. New York, NY: Crown Business.

Deutsch, M. (1973). The resolution of conflict. New Haven, CT: Yale Press.

Epictetus. (2014). Discourses, Fragments, Handbook. R. Hard (Trans.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Fisher, R. and Ury, W. (2011). Getting to yes: Negotiating agreement without giving in. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Hadot, P. (1998). The inner citadel: The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hadot, P. (2002). What is Ancient Philosophy?, M. Chase (Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Heath, C. and Heath, D. (2010). Switch: How to change when change is hard. London, United Kingdom: Random House Business Books.

Hughes, C. (2017). The ellipsis manual: Analysis and engineering of human behavior. Virginia Beach, VA: Evergreen Press.

Lewin, K. (1947). Frontiers in group dynamics: Concept, method and reality in social science; Social equilibria and social change. Human Relations, 1(5), pp. 5-41.

Robertson, D. (2010). The philosophy of cognitivebehavioural therapy (CBT): Stoic philosophy as rational and cognitive psychotherapy. London, UK: Routledge.

Rosenberg, M. (2015). Nonviolent communication: A language of life, 3rd ed. Encinitas, CA: Puddledancer Press.

Russell, B. (1930). The conquest of happiness. London: Routledge.

Sellars, J. (2006). Stoicism. London, UK: Routledge.

Seneca, L. A. (2016). Letters from a Stoic. R. M. Gummere (Trans.). Mineola, NY: Dover Publications.

Stockdale, J. (1995). Thoughts of a philosophical fighter pilot. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press.

Thompson, G. and Jenkins, J. (2004). Verbal judo: The gentle art of persuasion. Colorado Springs, CO: Quill.

Vecchi, G., Van Hasselt, V., and Romano, S. (2005). Crisis (hostage) negotiation: Current strategies and issues in high-risk conflict resolution. Aggression and violent behavior, 10, pp. 533-551.

Voss, C. & Raz, T. (2016). Never split the difference: Negotiating as if your life depended on it. HarperCollins.