My wife and I sat near the very last rows of the economy section of an Airbus 330-300, the big one, eight seats across. Within minutes I became aware of a willful, high-energy two-year-old sitting on the lap of its mother right next to me. The six-hour flight from San Diego to New York City had been unremarkable, the usual discomforts, but now I was about to be subjected to more than nine hours of squirming, crying, yelling hell. I felt sorry for myself for awhile, confined as I was to a sitting space not much larger than a straightjacket, but I put in my earplugs and reminded myself that soon I would never see this kid again. The mother had to deal with him 24 hours a day, every day. Ten minutes before we landed in Athens, he passed out.

A pilgrimage is not a holiday. With a pilgrimage there is purpose, determination, and respect given; not comfort, ease, and fun taken. Travel is often hard, food and accommodations are often unappetizing and uncomfortable, but that’s OK. In the place of fine dining and luxury one realizes a sense of accomplishment and of greater understanding, not just about the world but about oneself. The pilgrim on a journey feeds both body and soul.

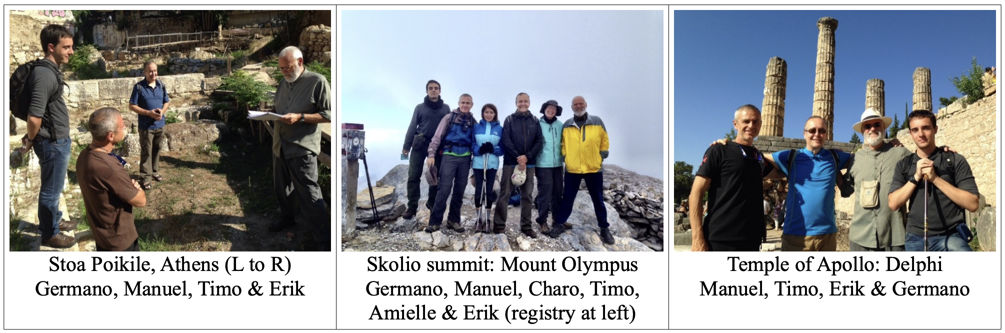

When we landed, our pilgrimage on the ground began. There were six of us coming from four different parts of the world: Timo Koivusalo, Finland, a graduating student of the Marcus Aurelius School; Germano Martinelli, Brazil, a recent graduate of the Stoic Essential Studies course; and, Manuel Trueba (aka Manolo), Spain, a Marcus Fellow of the College with his wife, Charo, a university professor; and, my wife Amielle and I from San Diego, California. Every pilgrimage needs a master logician and navigator, and fortunately we had one. Long ago, my wife Amielle demonstrated her special talent for these skills when she and I were traveling in Japan. I’ve never doubted her since.

A Christian pilgrim goes to Jerusalem; a Muslim goes to Mecca; the Stoic pilgrim may choose a number of places in Greece, but cannot claim to have come home until he or she stands where Zeno stood at the Stoa Poikile. Our pilgrimage, then, began in Athens where our philosophy began. Next stop on the itinerary would be northern Greece where we would attempt to climb Mount Olympus, home of the Greek gods. And, finally, we would head back to Athens, stopping on the way in the town of Delphi to see the Oracle. We all know that Socrates visited the Oracle of Delphi, and what she told him launched his life as a philosopher, but not everyone knows Zeno asked a question of the Oracle as well. More about that later.

Athens

Coming from four different directions we arrived at four different times. The first day, Wednesday, the 10th of September, 2014, Amielle and I arrived in the morning. Timo arrived later that afternoon. Manolo and Charo were coming the next day. Germano was already there but exploring another part of the country. All but Germano stayed at the Economy Hotel on Athinas Street, downtown. It was cheap, but clean, and even in September we were quite happy the air conditioner worked well. Bed and breakfast for about $75. A most reasonable arrangement and a popular one. If you’re planning to stay here it’s wise to make your reservations well in advance. The hotel is right behind Athens City Hall and right next to some porno video shops—a juxtaposition of politicians to pornography we all found curious.

Timo, Amielle, and I headed out first thing Thursday morning to be at the Acropolis early before the heat of the midday sun. After paying our respects to that ancient city on the hill, we went to the Agora (pronounced, ago-RAH), the markets and gathering places of that earlier time. Somewhere there we knew the Stoa Poikile would be, but we didn’t know where. We asked repeatedly: security guards, locals, anyone who appeared to be alert and aware, but no one knew. In fact, not only did they not know where it was, they didn’t know what it was. Even after we tried to pronounce it “correctly” (pah-keelee stoa), we got no looks of recognition.

Finally, we went to the Stoa of Attalos, a beautifully reconstructed stoa from about the same era. You can see part of the first floor at the top of the home page of the College website. When this image was chosen years ago, it was selected because it was a Greek stoa. At the time I didn’t know anything more. It’s a two-story building with massive columns and quite a lot of sculpture, especially on the second floor. Amielle went into the gift shop and asked if they knew where the Stoa Poikile was located. They didn’t know, but they did know that the American School of Classical Studies at Athens was located just above on the second floor, and surely they must know. Up we went. A security guard showed us to their door on the back wall, and I rang the bell.

It was answered by a middle aged American whose name will remain anonymous to protect his privacy. I asked if he knew where the Stoa Poikile was located and if it was possible to go down onto the actual excavation site. I knew from photographs taken earlier by John Kyriazoglou, a local Athenian member of New Stoa, that it was surrounded by wrought iron fences. He said that, yes, he knew where it was; but, no, he could not let us in. I explained who we were in some detail and that there were six of us who wanted to be there in that location for a graduation ceremony the next day. No, he said, that would not be possible. I kept talking. I told him it would be an informal affair—no funny hats or robes, no burning torches. We just wanted a few minutes to stand where Zeno stood and say a few words about how honored we were to be there 2300 years later, and to have a little graduation ceremony for Timo who had just completed the Marcus Aurelius School program. I told him about the College and kept talking until he finally said yes!

It was set for 10 AM the next day, Friday, the 5th. The six of us were waiting at the fence when he arrived and unlocked the gate. The American School man was the last one remaining of the 50-member excavation staff and volunteers of the year, and this was his last day before flying out to Sweden for a month. It was our only chance. If we had come a day later it couldn’t have happened. We stood exactly where he said Zeno probably would have stood. He had an excavation map and showed us the layout of where they had been excavating for many years, but were only down to the Byzantine era. I said a few words, handed out Timo’s certificate, took pictures, and we all stood there feeling what each of us was feeling. Afterwards, we had coffee and tea at an outdoor cafe just on the other side of the fence. The American School man had to rush off to close the Classical Studies office for the year. We looked at the Stoa Poikile and continued our thoughts—some of them aloud.

Mount Olympus

Next, Spilios Agapitos, also known as Refuge ‘A’ on Mount Olympus. It was the only time in my life, and I’m 69 or 70 years old, depending upon your philosophical point of view, the only time in my life when I was in a remote location that the purveyors of anything did not raise the rates far above what one would pay for the same thing in town. Refuge ‘A’, a stone fortress, about halfway to the summit of Mount Olympus from the trail head at Prionia, is where we spent the night. Food and lodging, dormitory style. Food and all other supplies had to be packed up the trail by donkey, and yet nothing cost more than it cost in the town of Litochoro at the foot of the mountain. I still can’t believe it.

From hot and humid Athens to cold and wet Olympus. There wasn’t any heat in the refuge. We had made reservations well in advance, highly recommended, and for that we got a dormitory room to ourselves. The six of us in bunk beds in one very cold room. We each were given three thick, wool blankets, and that turned out to be ample. There was a fireplace in the main part of the refuge, and earlier we had all huddled around, drying out our wet clothes from the hike on the first day. It had been raining or drizzling since we arrived. At midnight that night I woke up for some reason and saw our room bathed in a soft light. It was coming from the window, and I looked to see if someone was shining a flashlight in. It was a full moon. For a few minutes the clouds parted and the full moon shined down upon us. I took that as an good omen.

Up at 5 AM, packs repacked, a quick breakfast, and at first light we resumed our climb. 2917 meters was the original measurement, not a really tall mountain, but the tallest in Greece. The current, more accurate measurement is 2918.8 meters, but most still say it’s 2917. More importantly, it’s the home of the Greek gods. It is unusual in other ways, too. The Mediterranean Sea is not far away, you can see it from the town of Litochoro, and for a mountain this tall to rise up directly from sea level is rare. It’s not as high or as hard to climb as Mount Whitney in California, but there were moments.

One arduous stretch of what appeared to be about a kilometer in length was remarkably steep—heart pounding and hard breathing every step of the way. Normally, the original trailblazers in such a situation create switchbacks. No switchbacks, just straight up. Grueling, but at the end of it was Skala, the junction where you decide which peak you which to summit. Take the trail to the right and you can climb Mytakis, the throne of Zeus, a rocky promontory that is technically difficult with steep and sheer drop offs that are not for the fainthearted. Take the trail to the left and you can climb to Skolio, home of the next most important gods, such as Athena and Apollo.

It had been raining or drizzling the day before and part of the time we were in the final ascent, and there was no question that the Mytakis rocks would be wet and slippery. Although Manolo and Germano were undaunted by this potential danger, they decided to accompany the remaining four of us who were less inclined to hazard this rock scramble. We all turned left. Personally, I’ve always preferred Athena anyway, the more noble side of Zeus’s nature, and to celebrate our decision, the sun came out for just an hour or so, and we saw in all its natural splendor why Mount Olympus was and is a fitting home for the gods. We signed the book at the summit, had our picture taken, and descended back down into the mist and rain.

For those who read old travel information that often recommends hiring a guide to find your way. No, don’t bother. It’s entirely unnecessary. The trails are well marked from start to finish. The EU has funded quite an effort to mark the trail you want, the E-4, with signs that are clear and permanent—most of the time. But, if you have any doubt, just ask any one of the many hikers you will meet along the way. Mountain hikers tend to friendly and helpful about such things. We’ve all been there.

Delphi

We call it DEL-fi, but the Greeks call it del-FEE, and if you want to surprise the locals, just pronounce it as they do. Speaking of locals, a word should be said about getting around Greece and the welcome and assistance we received when we were there. Without exception, they were as helpful as they could be. That is, if they could help at all, they did. English-speaking Greeks are common, and whether we were dealing with strangers or our Athens contact, John Kyriazoglou, the people were invariably polite, friendly, and helpful. On more than one occasion locals went out of their way to make sure we were not lost. I wish there was some way I could thank each of them again for their many kindnesses to us. Although our ignorance and confusion was often apparent, we were never embarrassed or made to feel as stupid as we must have sounded.

The journey south from Litochoro to Delphi is complicated. Let that be a warning to those who may wish to retrace our pilgrimage exactly. Why it is so difficult I don’t know, but it required numerous changes of trains, buses and taxis to finally arrive at our destination. It was worth it, of course, but unless you have a logistics and navigation master in your group, as we did, be prepared to struggle. Delphi has been a tourist destination for more than 3000 years (they’ve discovered evidence that the Oracle has been prophesying futures since 1400 BCE), but they don’t make it easy to get there when coming down from the north of the country. It’s a straight shot from Athens, but if you go back to Athens, which is south of Delphi, then coming back north you’re going to have a very, very long day. We put our faith in the master navigator and cut the time of that long day in half.

This section could be called “Decompressing in Delphi.” Not only was it a wonderful way to recover from the effort of climbing Mount Olympus, but we found a quiet friendliness about this charming little town that served as a balm to the aches and pains in our calves and thighs. The Athina Hotel (that’s how it’s spelled), where five of us stayed, offered bed and breakfast for two nights that we would normally expect to pay for one. Delphi was without a doubt the least expensive part of the trip, and the first and last impression I had of it was of a colorful, picturesque, quaint, old world village with many shops, cafes, small hotels, good restaurants, and amazing views. Delphi is a mountain town, and the view from our balcony, for example, would cost the traveler dearly anywhere else in the western world.

I did have one complaint, but that was not unique to Delphi. Bathroom showers. Apparently Greeks don’t really care much about the idea or concept of the shower. Wherever we stayed the shower stall was nothing more than a platform with a hand held shower wand and entirely inadequate curtains. They had a drain in the bathroom floor, apparently because they know you will be making a watery mess all over the room. Plan to throw down all of your bath and hand towels to keep from stepping and slipping in pools and puddles that will collect after each shower.

It was the same in Athens, Litochoro, and Delphi—three widely separated towns in Greece. At the end of our pilgrimage we were looking forward to what we expected to find in the upscale hotel we rented for our last night in Athens. After all, we paid twice as much for it as we had for the Economy Hotel. It was listed as the number one hotel in Athens by one of our travel books, and it was an excellent hotel in an excellent part of town, but although they had marble counters and other aesthetic refinements, they still had a drain in the middle of the bathroom floor to deal with the flood emitting from the open shower. A small complaint, but one made larger by its very oddity.

The original oracle room in the Temple of Apollo, indeed the Temple of Apollo itself, and all of the surrounding marble buildings and monuments of antiquity, were in ruins, some just broken fragments of what they had been. We have a Christian Byzantine Emperor, I’ve forgotten which one, to thank for this. He wanted to make sure no one would ever go to Delphi to consult that pagan prophetess again. Even so, it’s still possible to ask the oracle a question, if you wish, and some of our party did. There are no village women sitting on stools over gases emanating from cracks in the earth speaking in obscure riddles and symbolic language, but you can still ask and listen for an answer. I sat on a bench in the shade of a little olive tree overlooking the ruin of the Temple of Apollo. I asked a question and waited quietly. In a moment or two my subconscious mind provided an answer, but unlike Socrates and Zeno, I intend to keep both the question and answer to myself 🙂

Oh yes, I promised earlier to recount what Zeno asked the oracle when he came to Delphi. Diogenes Laertius is the source that tells us Zeno went to consult the oracle. He doesn’t say which oracle, but the one at Delphi is what can be assumed when one is said to go to the oracle. In Book VII, chapter 1.2 of Lives of Eminent Philosophers, vol. II, D.L. says, “It is stated by Hecato and Apollonius of Tyre in his first book on Zeno that he consulted the oracle to know what he should do to attain the best life, and the god’s response was that he should take on the complexion of the dead. Whereupon, perceiving what this meant, he studied ancient authors.” I suspect that is how it came to be that Heraclitus became our cosmologist, but that’s pure speculation.

At the breakfast table on our last day together, conversation was subdued. When we finished eating I detected an unspoken reluctance to leave the table and go pack. Normally, we would all be eager to get up and face the next adventure, but this time no one was in a hurry. We were all taking the express bus from Delphi to Athens at 10 AM, plenty of time to pack. I don’t remember what we talked about exactly, mostly small talk and upcoming flight details. We didn’t talk about how strangers could come together in a foreign land and get along so well, even with warm camaraderie, despite physical, psychological, and mental efforts that would commonly test the best of friends. No one noted aloud that there had not been a single harsh word or hard feeling in these ten days of togetherness.

Amielle and I got on the plane the next morning, alone. We lost her tote bag on the metro ride to the airport—just forgot it and left it behind. Fortunately our tickets were in her purse, but our water bottles and snacks and some important work papers were gone. When we got to JFK, our entire two-hour layover was spent in serpentine lines going through security and customs. The plane left the gate and headed out on time. Twenty minutes later, while we were waiting to taxi down our runway, the pilot apologized and said we would have to go back to the gate for some documents that needed to be signed. We went back, then out to the runway again. After a long pause, the pilot apologized and said we would have to go back to the gate again. Apparently all the papers hadn’t been signed.

By the time we left New York City, we were more than two hours late. By the time we arrived in San Diego it had been twenty hours since we boarded our plane in Athens. We waited for our luggage at the carousel. It never came. We waited. It never came. The carousel stopped going around. We filled out the required forms with a young woman at the baggage claims office. A colleague sneaked up behind and tried to startle her. She stared at him. It was the middle of the night. Our climbing poles and boots were in that bag. We didn’t know if we would ever see them again.