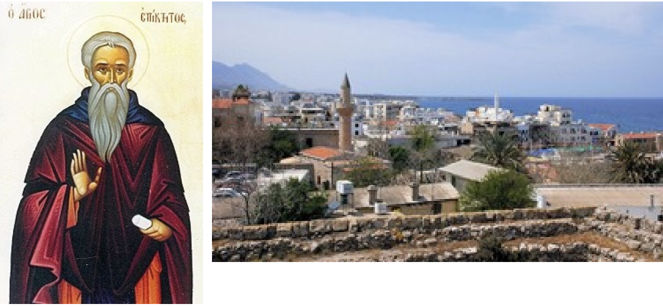

The popularity of Epictetus among some early Christians as a virtuous pagan is perhaps reflected by the fact that several Orthodox saints took his name. One such Saint Epictetus was a monastic martyr from Bithynia (north-central Turkey) during the reign of the Roman emperor Diocletian (284-305 C.E.). Another Saint Epictetus (12th century) was from northern Cyprus where a village called Ayios Epiktitos (the Turkish name is Çatalköy) still exists today.

The attitudes of Christians to pagan philosophy in the first four centuries of the Christian Era varied dramatically and from the very beginning from outright hostility to admiration. Tertullian (160-225 CE) in a famous passage from his De Praescriptione Haereticorum (VII) vividly attacked Greek philosophy, reminding his fellow believers that Christians should seek inspiration from the Stoa of Solomon, not the Stoa of Zeno. St. Clement of Alexandria (150-215 CE) writing at around the same time as Tertullian, on the other hand, viewed Greek philosophy as a kind of praeparatio evangelica, imperfectly pre-figuring the truth finally revealed fully in the new Christian faith.

The Encheiridion (Ench) of Epictetus uniquely resonated with some early Christians seeking to incorporate popular pagan teachings, especially of those of the Stoics, into apologetics directed at nonbelievers, as Christianity gradually became the predominant belief system in the Roman Empire. Epictetus’ apparent piety and ethical teachings meshed well with Christian thought. Epictetus himself seems mostly unaware of the Christian movement, although he may have mentioned it in Discourses 4.7.6, where he seems supportive of the ethical teachings of the new movement while denigrating the reasons put forward by Christians for their beliefs. Christian ethics were to be admired, but the underpinnings for those ethics (habit, madness, faith in revealed scripture) were inferior to the typical Stoic arguments (reason and the clear testimony of nature).

In fact, the Encheiridion of Epictetus was adapted for use as edifying reading in monastic communities during the Byzantine period (the fifth through the fifteenth centuries CE). The earliest extant manuscripts of the Encheiridion are Christian adaptions, not the original pagan text. I have always found this curious. Although there are many aspects of Stoicism, especially in its ethics, that bear similarities to Christian ideas, an even greater number of Stoic concepts stand in direct opposition to traditional Christian thought. This dichotomy may explain why some early Christians admired the Stoics, whereas other believers either denounced Stoics as atheists or at best viewed them with suspicion.

Many books about Stoicism or Epictetus mention that the Encheiridion was adapted for use in Chrisitan settings, especially in monastic communities (John Sellars, Stoicism, paperback, University of California Press, 2006, page 138; Robin Hard, Epictetus: Discourses, Fragments, Handbook, paperback, Oxford University Press, 2014, page xxv), but provide little other information about these adaptations other than to say that simple substitution of words and names (for example, God for gods or St. Paul for Socrates) played the primary role in their development. I have always been curious about the nature of these versions of the Encheiridion, but always ran into dead ends whenever I tried to learn more. As it turns out, the way that the adaptions were created is sometimes far more complex than just simple substitutions.

Happily, Gerard Boter (The Encheiridion of Epictetus & its Three Christian Adaptations, Brill, 1999) produced a critical edition of the Encheiridion and its Christian adaptions. Since this outstanding piece of scholarship is most likely only going to be found in graduate libraries and requires reading knowledge of both Greek and Latin (the Christian adaptations are untranslated), most casual readers will never be able to consult it. So I want to provide a better look at the adaptations for the un-Greeked and other readers without access to Boter’s book.

The oldest extant manuscript of the Encheiridion (Ench) dates to the 14th century CE, but there are three Christian adaptations, two of which pre-date that manuscript by many centuries:

- Nilus Ven. Marc. gr. 131 MS (11th century) = Nil

- Par Flor. Laur. 55,4 MS (10th century) = PC

- Vaticanus gr.2231 MS (early 14th century) = Vat

Each of these adaptations is represented by numerous manuscripts; so many, in fact, that Gerard Boter suggests (p. xv) that “the Byzantine world paid more attention to the christianized versions of the Encheiridion than to the original text.” The adaptations vary considerably in quality, as we will now see.

The Nilus adaptation (Nil) is generally of poor quality. Boter denigrates it as “a very sloppy piece of work.” (p.157) Its author christianized it primarily by deleting passages dealing with sexual matters or divination (although the cry of a crow, Nil 24 = Ench 18, is inexplicably still included), substituting obscure words with more common ones, and simplifying sentences. Apparently, the simple Koine Greek of the Encheiridion was still not simple enough for the monks. The names of Greek philosophers or mythological figures are usually omitted or substituted by an innocuous phrase, such as “a certain wise man….” Socrates usually becomes St. Paul, as at Nil 71b = Ench 51:

Ench 51

“This is how Socrates attained perfection, by paying attention to nothing but reason (logos) in everything that he encountered. But even if you are not yet a Socrates, you should live as someone who wishes to be a Socrates.”

Nil 71b

“Indeed, in this way Paul continuously advanced himself in all things by means of nothing else other than the Word (logos). You too even of you are not yet a St. Paul, you should live your life as someone who wishes to be a St. Paul.”

The Vaticanus MS (Vat) is even more ineptly and less consistently christianized than the Nilus adaptation. The author for the most part simply changed some specifically pagan terms and substituted biblical names for pagan names. For example, Socrates becomes St. Paul. Chrysippus becomes King Solomon. Anytus and Meletus, the accusers of Socrates in Ench. 53, become simply “evil men.” Terms associated with pagan cultic practices such as spendein (to pour a libation) become euchesthai (to pray), as at Ench. 31: “It is everyone’s duty to offer libations….” and Vat. 37: “It is everyone’s duty to pray….” Philosophers become philosopher monks.

The Periphrasis Christiana (PC) adaptation is by far the best (and the earliest) of the three attempts to christianize the Encheiridion. Some of the obvious changes common to all three adaptations are present: changing the plural gods (theoi) to the singular God (theos), simplification of grammar and vocabulary, and the substitutions for pagan names. The author changes Socrates to the Apostle or even apostles and martyrs. But what sets PC apart from the other two adaptations is that the PC author does not simply delete passages containing inappropriate pagan ideas. Instead he often substitutes Christian doctrine for the offending passage. For example, the chapter on loss and death in Ench. 11 becomes a commentary on Job 1:21 (“The Lord gave, and the Lord has taken away.”):

Ench 11

Never say of anything, “I have lost it,” but rather “I have given it back.” Has your child died? It has been given back. Has your wife died? She has been given back. Has your property been taken from you? Well that too has been given back. “But the one who took it from me is a wicked man.” What concern is it of yours by whose intervention the giver asked it back from you? As long as these things are given to you, take care of them as things that belong to someone else, just as travelers mind the inn.

PC 14

In the case of nothing say, “I have lost it,” but rather “I have given it back.” Has your brother died? He has been given back. Has your property been taken from you? Well that too has been given back. But you are upset that the one who took it is a wicked man. What concern is it of yours by whose intervention the giver asked it back from you? Having learned this lesson, Job said, “The Lord gave, the Lord has taken away.” “It is unjust,” it is written, “to resist the one who wishes to take back what he has given.” And also keeping in mind what is proper, it is written, “So seemed right to the Lord, and thus did it come to be.” For, indeed, if you truly determine that it is the Lord who ordains this, bear the will of your Master gently. For thus is the law for the slave toward a good master. Indeed, until these things are given back, be mindful of them as if belonging to someone else, just as travelers do of the inn.

Boter draws particular attention to the last chapter of the Encheiridion and how the PC author used it. Let’s look at the closing of the Encheiridion and how the author of the Paraphrasis Christiana skillfully adapted it for Christian use.

The original text of Epictetus:

(53) On every occasion we should have these arguments at hand:

Guide me, O Zeus, and you, O Destiny,

To wheresoever you have assigned me;

I’ll follow without hesitation, or if my will fails,

Because I am bad, I’ll follow nonetheless. (Cleanthes, Hymn to Zeus)

Whoever rightly yields to necessity

We accord wise and learned in things divine. (Euripides, Fragment 965)

‘Well, Crito, if that is what is pleasing to the gods, so be it.’ (Plato, Crito 45d)

‘Anytus and Meletus can kill me, but they cannot harm me.’ (Plato, Apology, 30c-d)

The original closing as composed by Arrian from Epictetus’ lectures simply provides several disjointed, edifying quotes from Cleanthes, Euripidies, and Plato that all Stoics should remember. The Periphrasis Christiana, on the other hand, intelligently weaves these bare quotes together into two brief, cohesive chapters, carefully linking them, and christianizing them as well.

The Christian adaption as found in the so-called Paraphrasis Christiana:

(70) In every occasion and every test that comes our way, we should have at hand to say: Guide us, O Savior, You and Your Holy Spirit, to wheresoever and however is pleasing to You. For we will follow without hesitation. Even if we are unwilling, because we are bad, we will follow nonetheless.

Whoever follows God willingly and obediently is wise in our eyes and dear to God. What is dear to God, we pray this to come to us.

(71) For if we live in this way, it is impossible for us to be harmed by anyone. Even if some people conspire together, and even if they go beyond assaults and persecutions, and even plot to murder us, they can indeed murder us, but cannot in any way harm us except in their own estimation. Yes, indeed, as the Lord proclaimed of those unable to cause us harm: “Do not fear those who can kill the body, but are unable to kill the soul.” (Matthew, 10.28)

As is fairly obvious, the Nilus and Vat adaptations often resemble little more than a basic Search and Replace operation in a word processing document. The author of the Periphrasis Christiana, however, carefully read his source material, the original Encheiridion, and adopted a more thoughtful approach to his adaptation. You can detect an active intelligence behind the changes he made to prepare the Encheiridion for his monastic brothers.